Tesla’s innovation is in the doghouse

And that’s a good thing.

Watching the world’s automakers respond (or not, as the case may be) to Tesla, has been interesting, to say the least. I find it fascinating to see an established market watch a competitor waltz in and secure a beachhead in a successful new category, with a near-zero response from the established powers for years.

All the while, the upstart works hard, establishes a brand, creates a supply chain and builds out proprietary charging infrastructure, not to mention (at the time of this writing) amassing the largest market capitalization of any US automaker. Even today, some of the largest, most advanced automakers are projecting they won’t be fully engaged in the electric market for another 2–3 years. So what does Tesla know that seems to baffle other automakers? Well, after having had the opportunity to drive a Tesla Model 3 for a few weeks, one thing hit me.

The difference between cats and dogs.

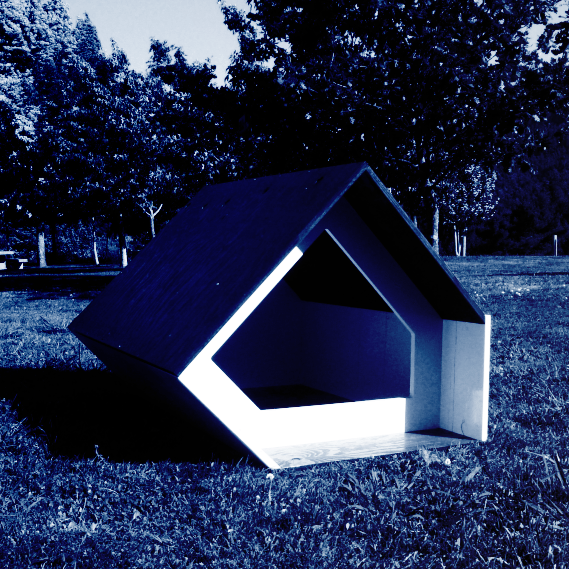

A genetic study of cats showed cats are basically unchanged from their feral ancestors. Meaning, they’re not technically domesticated. Well, they’re domesticated as much as they choose to be. And while people may derive a great deal of enjoyment and feel a great deal of empathy for their cats, the relationship isn’t in any way truly servile. In fact, it’s probably more accurate to say people are in service to the cats. Dogs, on the other hand, are the most genetically domesticated animal on the planet. And while not totally selfless, they are, for the most part, living in service to their owners. Why do I bring this up? Well, for almost a century, owning an automobile was more like owning a cat. It may be a rewarding relationship for many people, but ultimately, the human was the last consideration in the design, basically placed by the engineers into the mix in service to the machine. The car would do what it was asked, but it was, itself, never much help in the process. The innovation that differentiates Tesla is to design the car experience to be more like owning a trained dog. It’s a car in service to the driver.

Obviously, in that sense, self-driving comes to mind. But that’s not, in and of itself, what I’m referring to. Traditional automakers seem to start the design process by thinking about the machine itself—achieving a level of performance, adding a feature, etc. Tesla seems to have started at the experience and worked back to the machine needed to satisfy the vision for the experience.

For example, when the driver enters a Tesla, the car remembers and restores positions for the driver’s seat, driver’s sideview mirror and steering wheel steering mode, regenerative braking preference, mirror auto-tilt, instrument panel layout, performance preferences and all touch-screen display preferences, just to name a few. Pretty much anything you can set to your liking will automatically switch to suit you the moment you get into (or rather, your phone gets into) the car. The car adjusts to you.

When the car needs charging, not only will it remind you, it will show you where the nearest supercharging stations are, and, assuming you paid for the (inaccurately named) auto-pilot software, like a sled dog, will effectively assist you in getting there.

Enter the big dog.

The latest example of this perspective is the deeply polarizing Cybertruck. The first reaction most had to its unconventional design was of shock, even horror in some cases. However, when one considers the user experience as the main driver of the design process, a certain beauty emerges. The utility that the Cybertruck is poised to deliver is currently unmatched by any traditional truck maker:

Up to 14,000 pounds of towing capacity (tri-motor version)

120- and 240-volt outlets that can be used to supply power tools without the use of a generator

An onboard air compressor for tools

Adaptive air suspension

“The vault”: A motorized rollout cover that secures the bed; Tesla claims a solar-panel version should be available in the future, providing up to 15 miles of charge in a day

An innovative tie-down system that allows you to insert anchor or mounting points in various positions

Zero to 60 mph in less than 2.9 seconds (tri-motor version), 4.5 seconds (dual-motor) or 6.5 seconds (single-motor rear-wheel drive)

The whole announcement reminded me of a movie from the early ‘90s, “Crazy People,” starring Dudley Moore as an advertising executive in a midlife crisis. In the film, he pens what he considers an honesty-based headline for Volvo, which read: “Volvo: they’re boxy, but they’re good.” I have a suspicion Elon Musk would be quite happy with that headline, with perhaps the exception of wanting something more superlative, possibly incorporating a few well-chosen explatives in place of “good.”

I have a hard time imagining the Cybertruck coming out of the design shops of any of the major automakers. Though I also imagine those same automakers are having a hard time understanding how Tesla received more than 200,000 pre-orders for the vehicle within days of launch.

Empathy is an evolutionary advantage

Recent studies suggest empathy is what led to dogs being the most successful domesticated animal on the planet. And it seems that is what’s driving Tesla’s market success today. It will be interesting to see if the traditional automakers reveal themselves to be more akin to the dinosaurs or a pack of wolves waiting for their moment to pounce.